This year, I was appointed to Co-Chair the Urban History Association’s Early Career Committee, where I support young professionals and graduate student members through advocacy, programming, and professional development. This month, we held our first public programming: a first-author roundtable with a group of emerging scholars. Our panelists — Destin Jenkins, Rebecca Marchiel, and Gabriel Winant — joined us in a meta-discussion about publishing urban history research during our ongoing pandemic. Their texts show how legal concepts like municipal bonds, mortgage debt, or labor arbitration allowed financial investors to intervene in urban development and create the metropolitan landscape for our contemporary crisis. Their insight and advice illuminate how early career urban historians can advance research of value.

Category: Uncategorized

Diggin’ in the Crates: Community Archives in Suburban History

Last month, I was gifted with an opportunity to present some research at the annual board meeting for the Arizona Historical Society. This was an immense honor – some of my earliest archival research occurred in their collections. It was such a blessing to share my findings with this community and I am deeply appreciative that they chose to recognize my scholarship in this fashion. Below is a YouTube clip of my address. I hope you all enjoy it as much as I did.

My New Job

—

I vividly remember getting my application to Howard submitted at the deadline. I was a National Achievement Finalist due to my SAT scores – which were pretty decent, not worldbeating, but best in my class – and they offered scholarships for all Finalists. So, during basketball practice, my dad picked up my application and took it to the post office. I ran out to the parking lot in the middle of warmups, my sweaty body shivering in the February chill, knowing in that moment my life had taken a new trajectory. I mean… I didn’t know. But I still remember that parking lot because, even if I didn’t know, I understood that I had charted a new course.

At that time, I wanted to work as a history professor at Arizona State University. I saw myself going to Howard so I could do that. I mean, I didn’t want to ATTEND Arizona State. Most of the students in my class went to school in-state. I was tired our local education. I wanted something more challenging; I wanted to feel connected to my curriculum. But I heard of a Black history professor at ASU and that sounded nice – a cool job with the comfort of home. That vison became my objective.

My dad and I drove to campus from Glendale. We left (from my recollection) on August 16, 2006. We stopped and said bye to my mom at the Denny’s on 27th/Bell. She was crying and had been trying to avoid me so she wouldn’t. But we said our goodbyes, and we drove away, and I fell asleep listening to Flyleaf as my dad drove us up the I-17. I started driving on the Navajo nation, but got pulled over pretty quickly, so my dad did most of the driving after that. We had planned to drive straight through but stopped for a night in Memphis. So we had to drive about sixteen hours, through the night, to get to DC by 9am on August 19, 2006. We arrived at 8:45am.

I was homesick for the first two years. I did a transfer semester in Tucson – not Tempe – but went back to Howard because I knew it was my best shot of getting into Grad school. I did – I went on to become the first HBCU grad to get a history Ph. D. from Penn – and had transformative personal experiences along the way. Had some girlfriends, had some breakups, had some good times, had some bad times – I even had a kid – but all the while I just wanted to go home and teach history at Arizona State.

When my fellowship ran out I did just that. I taught at community college and at ASU West. I started my research career as an unpaid assistant there, so things really came full circle. As I was finishing, I was a finalist for a Lecturer position at the Tempe campus, but didn’t receive an offer (probably because the person who got the position was a wonderful candidate) after an interview when I was asked why I wouldn’t leave for a tenure track job when one became available. Well, I took a couple postdocs, and declined lecturer opportunities when I had better opportunities out of state. But I kept applying for tenure track jobs, and was crushingly denied in search after search. It was all politics – of course – but they left me unemployed as the pandemic ended hiring opportunities. I took a forced sabbatical – really, I declined adjunct work – until I was offered an Honors Faculty position in Barrett, the Honors College at the Tempe Campus.

—

Today, Thursday, August 19, 2021, was my first day as a full-time faculty member at Arizona State University. I have been crying all morning. It isn’t JUST that I accomplished this goal I set out for – because it’s not really done, in a way, there is more that I can do to fulfill that vision – but because I arrived in DC fifteen years ago with this objective. It’s such a long time.

I have taken my son to the office twice this week. And I told him much of this story above. But today, I dropped him off at school, smoked a bit, stopped in a parking lot to cry my eyes out. It is hard to feel proud of myself right now. I feel like… so ashamed of who I am. I don’t like who I am right now. And I am exactly where I always wanted to be. Like, the sacrifice, the loss, the pain, the struggle… was it worth it? “I would have so many friends if I didn’t have money, respect, and accomplishments.” I need new friends, to replace those I lost, on the way to what? A lecturer position?

I dropped kiddo off late. He woke up late. We left without eating breakfast and got food at McDonald’s. Why am I not super timely? Or organized? Or someone other that who I have become if who I have become is so flawed? But these flaws helped bring my vision to reality. These flaws made it so that, fifteen years later, I could fulfill my vision for myself – that I could be a professor at Arizona State. The same vision which kept me in school after having a kid. The same vision that bet on postdocs over the tenure-track(!). The same vision that loves vice, and sin, and is clouded by shame when others know that I see these things. Because, for better or worse – opaque or perspicacious – I see what is in my line of vision. It’s real to me.

At Barrett, the Honors College, we are “dedicated to the dedicated.” Whatever that means. But it does mean something – these honors kids, the ones who want 102% in bio, the ones developing drug habits to study, the ones who… in their precocity… often kill themselves trying to please others.

To them I say – you are already enough. Your habits that brought you will carry you forward – make sure they are habits that will sustain you. This race of life is so long that you would not want to win it all at the beginning.

—

As a postdoc, one of my senior colleagues said, when it came to the job market, that “N=5.” At first, I didn’t understand what they meant, but basically, they were saying that you have five years after finishing your degree to land a tenure-track gig. Well, in some ways, the pandemic was actually a gift year, because on August 21, 2023, a little less than six years after earning my Ph. D., I accepted a tenure-track position as an Assistant Professor of African American Studies at Northern Arizona University. This amazing opportunity, too valuable to pass up, came with the bittersweet realization that my time at ASU had come to an end. This had been my dream institution for the past decade – my hometown university, where many of my family and friends had attended class, a place to bring my local interests before a local audience – but it no longer offered a position that accommodated my professional ambitions. And I’m okay with that. It was an honor and a privilege to work at Arizona State University.

But the sentimental optimism of my youth… where has it gone? Has it hardened and calcified like petrified wood? Or have I hidden it, even from myself, to protect that precocious teenager – the one who decided to become a scholar all those years ago – from the petty, vindictive hatefulness that saturates academia? All I know – I used to love tests, then I feared assessment, but now… I’m looking forward to future challenges.

I used to think that teen had proved his worth by getting a scholarship, and I couldn’t understand why things were so hard for him as an adult – I even saw him as a failure – after he had success as a kid. But he did prove his capability, not for anyone else, but for his own understanding, and I find peace knowing that each challenge is an opportunity for his brilliance to shine again and again and again and again and again and again and again…

ad infinitum

Why Juneteenth Matters

On Juneteenth, I was able to join my cousin on her YouTube channel last week to discuss the history behind this new federal holiday. We had a wonderous chat about Juneteenth and the importance of Black holidays. It was a joy to join in this livestream – please subscribe to her channel for more content like this!

On Refunding the Police

Right now, everyone wants to defund the police. And in some ways, we should. We should defund them of taxpayer money for wrongful death settlements. There have been hundred of millions in public money spent on wrongful death and civil rights settlements against our police departments. Public money shouldn’t be spent on these settlements. There are other potential areas where these resources should go – like human services – and it is counter-productive for our cities to spend money on racism. We need communities where safety – not fear – produces law and order. So, instead of defunding the police, and removing that money from the public coffers, we need the police to refund monies that can be used to house homeless people; to encourage mental health interventions among our youth; to improve our bus stops, and parks, and libraries; to get counselors – not student resource officers – in our schools. This will bring more safety – and less fear – in our communities than continuing to pay for consent decrees or armored vehicles.

Social Justice and Settler Colonization: Black Women and Black Newspapers in the Metropolitan Southwest

This spring, I began working on a new project about the Valley of the Sun. The American southwest has served as a site for phenomenal population growth in the 20th century. People from all over the globe settled in this region as Sunbelt development attracted human capital. Civic activists helped settle urban areas through their collaboration with elected officials, organization of community members, and protests of racial discrimination. The Black press, due to their nexus between the business-class and community activists, provides insight on how racial minorities navigated the urban Southwest.

This project, specifically, focuses on the how the activism of Black women was represented in the Black press. Civic activism by Black women complicates the concept of settler colonialism to show how marginalized people fought to make the urban Southwest more inclusive while advancing settlement of colonized territories. My primary focus is the Black Dispatch, a newspaper published by Marian J. BeCoates during the 1976 bi-centennial year. In February, we recorded an oral history interview that explored her time in the publishing business, her previous military career, and her experience as an ASU student.

The Black Dispatch was covered by the Arizona Republic during Black History Month, but unfortunately, their coverage overlooked contributions made by women of color like Jesse BeCoates. Thankfully, through collaboration with the Emerge Collective, we were able to recover this valuable history and fill in gaps in the historical record concerning Black women in Black Phoenix newspapers.

A 4/20 Memoir

Today, Derek Chauvin was convicted of murdering George Floyd. I was asked to give a reporter a quote. I said,

“Last summer’s protests made justice possible for George Floyd, only to recall how Dion Johnson, Breanna Taylor and Trayvon Martin never received the same grace… In many ways this verdict is the exception that proves the rule. It took thousands of protests to get one conviction, but if what happened to Floyd was a criminal act, then law enforcement continues to protect criminals in their ranks without accountability or apology. Hopefully, this verdict lays the legal framework for a more just and peaceful future between the American people and the police officers sworn to protect us.”

It freaked me out to read that in print. I started thinking about what it meant.

When I was a child, there was the Gang Resistance Education and Training (GREAT) camps at our elementary school… which was different from D.A.R.E (which was about drugs… not gangs). Basically, they told us gangs were bad, and that people joined them because they didn’t care about their family, and basically discouraged us from joining any gangs. Meanwhile, when I moved to my unified school district, there was a blanket dress code designed to prevent gang apparel from appearing on campus. No backwards hats, no wave caps, nothing that was associated (in their mind) with gang culture. Now, this was traumatic for me, because it represented an erasure of my cultural practices. But during this period, gangs were seen as a public crisis, and Black students did not organize to protest these restrictions.

But lo and behold, when I get to middle school, I come to find that there are two “gangs” in my eighth grade class. The Pinecones and the Honeycombs… something like that. Lord knows they weren’t taking it seriously – except some of my classmates really did have family affiliated with gangs. I didn’t know this back then, but when one of my friends joined their fun, I looked at him horrified, like, “But don’t you love your family?” Because, I had G.R.E.A.T. in my elementary school district, which was transitioning to serving communities of color, while we had D.A.R.E. in my predominately-white unified district. We talked a lot about drugs, but very little about gangs, and the values that had been jammed down my little throat were no where to be found among my white counterparts. They missed out on that indoctrination.

I thought about the murder of Star Johnson. He was a Black officer killed in the line of duty, back in the forties, when he was murdered by a white officer. These articles by Jon Talton do a wonderful job of explaining, but essentially, Johnson was killed while writing a traffic ticket to an off-duty detective. “Frenchy” Navarre claimed that he shot Johnson after the beat officer cursed him and started to pull his revolver, and his daughter would later allege Johnson had been hired to murder her father. Still, this death had to go before a jury trial, because Navarre shot Johnson five times downtown during lunch hour, and the prosecution was able to produce eight witnesses to support a guilty verdict. Talton finds that these witnesses faced threats and intimidation on their way to trial, and since several of them were people of color, their assertions broke a white supremacist taboo. African-Americans could not testify in court against white defendants in much of the United States, and due to this civil inequality, often failed to gain convictions when killed by white perpetrators. True to form, Navarre was acquitted and returned to his job at the police department.

From here, however, history moves forward. When Navarre returns to work, he is killed by Joe Davis, who had been Johnson’s beat partner. Upon shooting Navarre, Davis holed up in the city jail and refused surrender to anyone other than the Police Chief. Talton claims that Davis openly shared his plan to murder Navarre if “the courts” didn’t deliver the correct verdict. Many of the downtown merchants felt sympathetic toward Davis, as he allegedly argued that he shot Frenchy in self-defense, but he was eventually convicted of manslaughter. Talton finds that these actions reflected complaints arising from nearby Black soldiers after a racial uprising against alleged police brutality two years prior.

But, pertinent to our time, the Navarre estate argues that this was little more than a cartel dispute. But the ambiguity that arises out of this claim lays clear how law enforcement served as a haven for white criminality. Navarre either was murdered due to a hit put out by organized crime, or he got away with killing a black officer in a community already reeling from a racial uprising. These contradictory truths both suggest that our police forces were corrupted. Why would we believe that a similar conundrum could not be at play today?

Moreover, there is ample evidence that law enforcement has been providing cover for illicit and illegal activities. There is sufficient evidence out here that corruption widespread without casting blame on a single officer or department. We are facing a systemic conundrum – how do we trust that there are “good” cops when we see officers escape punishment under a judicial system that has shown rank indifference toward the value of Black life. This is a critical crisis of confidence and allows for more grandiose speculation to occur.

So, when I think of the officer who killed Dion Johnson, with multiple use of force allegations yet never having to face the public that claims abuse, it leads me to conclude that there must be more criminals within law enforcement. Not even because we have evidence of organized activities, but because we have evidence of a willful disregard for humanity that – when unchecked – proves ripe for criminal infiltration. Moreover, as we saw with the Chauvin trial, it is possible for a jury to decide that an officer commits a violent crime against civilians, which few officers have had to face dur to protection by their peers. While convictions are rare, we are seeing how law enforcement – while well trained – make anodyne mistakes like many civilians. But the protection of this entire class from similar scrutiny faced by civilians during these encounters creates a power disparity that can monetize violence. Our law enforcement is so powerful that they inspire fear due to their ability to elude justice. That is the exact reputation necessary a successful criminal syndicate.

When I have to engage with law enforcement, I put my hands up and state that I am unarmed. I usually am unarmed when dealing with law enforcement. I want all of us to make it out of that encounter safely. I do not think that they are planning me harm… I’d like to believe people I encounter do not practice that type of evil… but my safety is not guaranteed in these interactions. In a moment, a spark, a flash, a bang, and it becomes his word against mine. What Navarre believed, and his trial shows, is that white officers were not held accountable for police violence that targeted communities of color. The testimony of an officer carried more weight than any other witness, and as the conviction of Davis showed, this status conferred white officers with privileges that black officers did not have. This continues into our time, as shown by whistleblower cases where Black officers are expelled from the force for confronting internal corruption, and reflects a systemic bias that could – possibly – be unintentional but is better explained as good ol’ fashioned white supremacy. This system sustains power inequalities that breed corruption, and civilians have not been able to decide if much of this behavior is criminal or not.

So, I don’t think that I’m off in my assessment. If anything, I would want to hear from Black officers about what we, as civilians, can do to help root out corruption in law enforcement. We need a way to determine who the good cops are at this point, and one way of doing that is by removing bad cops from the force, and determining “bad” on the basis of community input. If officers are to serve our community, we can’t live in fear of them, because distrust creates too many opportunities for exploitation and abuse, so we need officers to promote peace (not compliance) when engaging with civilian populations. That requires a radically different approach to policing – one that reduces violent outcomes during casual encounters between civilians and law enforcement. But, lacking this mechanism, we live in a system where many civilians are terrified of the people sworn to protect them. The onus for change is not on the part of the citizen, but instead, it is on our law enforcement agencies to expel agents that do not equitably encourage peaceful resolutions between civilians and the state.

Our children deserve a more just and equitable world that the one we have inherited. I hope that we can reconsider how violence operates in our society.

Black Women’s Arts and Culture Summit

March, as Women’s History Month, is a wonderful time to celebrate Black women emerging as mainstream arts leaders in Phoenix. The Emerge News Collective hosted Chanel Bragg, Seretta Presswood, and Danayshia Smith in a conversation on the role of Black Women in our Arizona Arts and Culture scene.

Then and Now: Lessons Learned from MLK–Love as the Practice of Freedom

“The use of violence in our struggle is both impractical and immoral. Therefore I would strongly urge… a cessation of the violence and lawlessness presently existing and recognize the power of nonviolent resistance.”

–Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the wake of the 1964 Rochester Rebellion

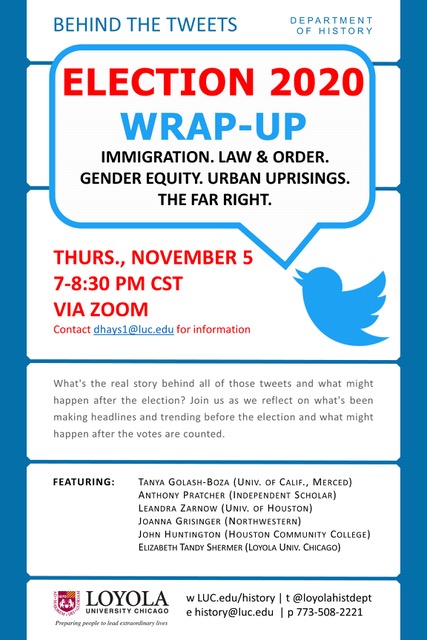

Post Election Wrap-Up

We were hoping that this discussion would be election wrap-up but it looks like it will be more like ongoing analysis. Anyway, if you have time this evening, check it out. I’ll be providing historical analysis on how Arizona became a battleground state.